Pre-Regatta park arrests highlight police targeting of unsheltered people in Charleston, W. Va.

An investigation into the arrests of 16 unsheltered people in a single hour shows the City of Charleston is 18 months into a spree of trying to address homelessness with zero-tolerance policing.

Aug. 17, 2023 • Written by Kyle Vass

On a warm night in late June, Dustin Thomas was walking near the Clay Center in Charleston when he noticed police arresting several people in the nearby Mary Price Ratrie Greenspace. Their crime? Being in a park after hours.

“The first person they grabbed was a young girl who has a lot of mental health issues. I knew she wasn’t going to be okay. So, I yelled out ‘Hey, what did she do?’” said Thomas, an unhoused U.S. military veteran.

A Charleston police officer then waved him over. And when Thomas stepped into the park as directed, he said officers immediately began arresting him for being on the grounds after hours as well.

Thomas went on to spend the next six days in one of America’s deadliest jails, crammed with two other men in a cell designed for one person.

“They put three people in a cell for one,” he said. “It’s just so dirty because everyone has to use the toilet there all the time. And you only get two showers a week. It’s filthy. And I told them I have a history of MRSA [a type of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infection] and they didn’t give a shit.”

Body-worn camera footage obtained by Dragline shows Thomas telling officers he was on the sidewalk, but doesn’t show any other parts of his interactions with police. The footage, obtained by Dragline through the Freedom of Information Act, shows numerous other unhoused people being arrested that night.

“You are in the park while it is closed!” an officer shouts at a woman, inches away from her face. She shouts back, “I didn’t know!” while crying. Within a few minutes, she’s packed into a police transport van. Footage shows her shaking, repeating, “I’m not okay. I’m not okay.”

On June 29, as the city was preparing for the annual Sternwheel Regatta, a multi-million-dollar festival that attracts thousands of visitors to the city, Officers Christopher Cooper, Josh Harper, and a handful of others with the Charleston Police Department entered three city parks in the early morning hours. Before the sun rose that day, officers arrested 16 people, all of them unhoused.

Footage from Cooper’s camera showed that in each instance, few words were said. “Get up,” an officer grumbles at a sleeping couple before taking their dog. “Is this your all’s shit?” he says. “Yes, sir,” they answer.

One by one, officers walked the people, many of them half-awake, into a transport van. The officer driving turned up the stereo. “Come Back Home,” a hymn by John W. Peterson, blared over the speakers.

See His arms outstretched to you. Welcome.

Come back home. He waits to pardon you.

As the van rolled out of the frame, an off-camera officer asked, “What’s he playing?” “One of his slow songs,” Cooper replied as the two laughed. John. W Peterson bellowing through the empty streets of pre-dawn Charleston, the van set off; first to the police station and then to South Central Regional Jail.

The 16 unsheltered people who were arrested for being in a park at the wrong time of day were processed at SCRJ one day before Regatta. They stayed there without a bond hearing until the festivities wrapped up six days later.

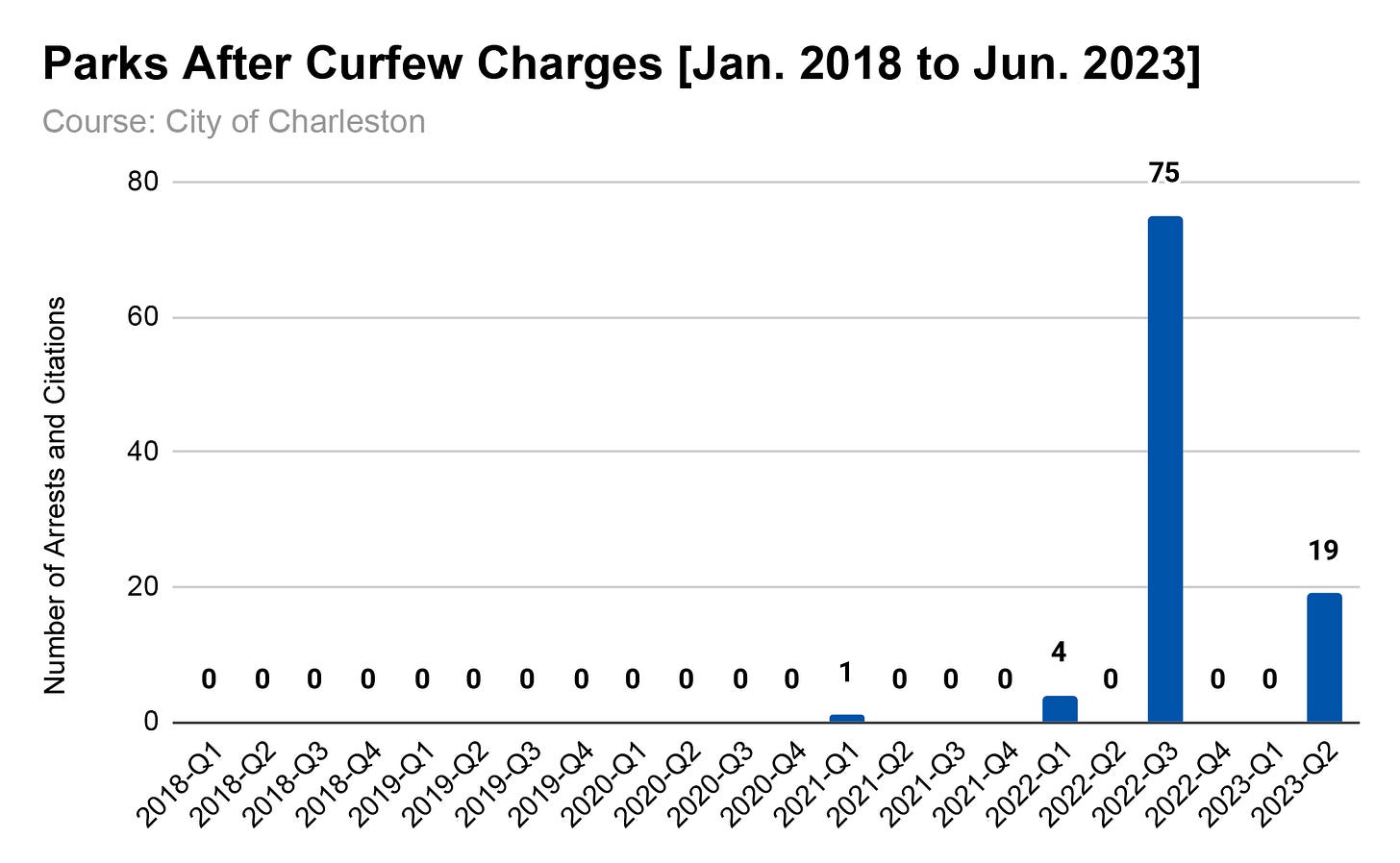

For years, Charleston’s law against being in city parks after 11 p.m. (9 p.m. in the winter) has remained all but unenforced. For example, from 2018 to the end of 2021, just one person was charged with this offense. But the enforcement of this ordinance along with other laws that disproportionately affect unsheltered people has skyrocketed in Charleston of the last year and a half.

In January 2022, a few months after Charleston Mayor Amy Goodwin unsuccessfully called for a special session of the West Virginia Legislature to deal with homelessness, Charleston police started using a handful of low-level offenses (the parks curfew, littering, and jaywalking laws) to embark on a spree of giving tickets to and arresting unsheltered people.

Over the last year and a half, the enforcement of these laws has climbed 2,600 percent. By comparison, the enforcement of most other crimes has remained consistent according to a review of five years of CPD data obtained by Dragline through a Freedom of Information Request.

Officers Cooper and Harper – the police who arrested the 16 unhoused people in the parks – were listed as the primary officers for nearly half of these charges during this wave of enforcement. And according to people interviewed for this story, the way these two officers (and a handful of others) are enforcing these charges is custom-tailored to target unhoused people.

Through background conversations with service providers, Dragline was able to independently verify that all but one of the 98 instances of people being charged with the parks after hours ordinance over the last year and a half months involved people who were unhoused at the time of being charged.

During this time, Charleston police have also begun giving jaywalking tickets to people who are panhandling. One man, who spoke on condition of anonymity after pleading guilty in municipal court moments earlier said, “I was holding a sign. Then, when I stepped out to take the money from a car, an officer rolled up and hit me with jaywalking.”

Despite two proposed anti-panhandling ordinances failing to pass when introduced to Charleston City Council members in recent years, police in the city have found a workaround.

Four other people who appeared in municipal court on recent jaywalking charges and several unsheltered people said they too had only been ticketed for this offense exclusively while panhandling.

Charleston police have also begun handing out littering citations to people who have simply set their belongings down by their feet or by their side when they sit down. Some have received littering tickets just for being near trash that was already on the ground.

In recent years, it was common for police in Charleston to write one littering citation every two months across the entire department. Since the beginning of 2022 however, officers have been writing 20 times that amount.

A Coordinated Effort

The city’s event coordinator for Regatta, Miranda Dillon, discussed the park raids with Lt. Mark Kinder three days before they happened, according to an email obtained by Dragline.

Dillon sent the email to Taryn Wherry, the director for the city’s quick response team for homelessness. Dillon relayed to Wherry that the Charleston Police Department wanted her to reach out in case the police — not the unsheltered people — “needed someone there to assist in the areas” during the raids. Dillon, Kinder, and Wherry ignored repeated requests for comment for this story.

Cooper’s body camera footage from the park raids also showed officers talking about a decision by the municipal court to close courts beyond the public holiday — a move that would lengthen the jail stay for those arrested from six to seven days.

Police knew about the court’s plan to lengthen its closure before the public, those arrested, or their attorneys.

One officer can be heard questioning another about the merits of keeping people in jail for that long. “Are they sending all these people to jail?” he asked. “Yeah, until next Thursday,” a second officer answered with a scoff. After a pause, the first officer replied, “You know what? It ain’t gonna do no good.”

Four days after the arrests Charleston City Council held a regularly scheduled meeting. Rachel Rubin, who at the time worked for the Kanawha County Public Defender’s office, addressed the council, calling out the timing of the arrests.

“This is now the second year in a row that in order to have its big party that the city has undertaken an entire effort to disappear anyone they don’t want to see ahead of the Regatta,” Rubin said referring to the heightened enforcement of these same crimes in the runup to the event a year prior.

Rubin also informed the council that her office had filed emergency bond motions to try and expedite release, requests she said went ignored by the city’s municipal court.

Docket reports and emails from court officials obtained by Dragline confirmed Rubin’s claims that the court removed cases from its docket on Wednesday. Municipal Court Judge Matt Smith ignored requests to comment for this story.

Amid pressure from Rubin’s office and the American Civil Liberties Union of West Virginia, the court rescinded its plan to close an extra day, returning cases to the docket and allowing the people arrested in the park raids to finally have a bond hearing.

Selective Enforcement

At 11:58 p.m. on July 2, Dragline observed three Charleston Police officers enter Mary Price Ratrie Greenspace – the same park they arrested Dustin Thomas in earlier that week. Police told a small group of unsheltered people that being in public parks is an arrestable offense and told them to leave. Police remained on scene until everyone left the park.

Later that night, however, Dragline observed two other public parks where police weren’t enforcing the parks ordinance.

At 12:21 a.m. at Haddad Riverfront Park, Regatta-goers lingered. Passing freely between docked boats and the park, they imbibed alcohol in public and belted “Sweet Caroline” without police intervention. (One person interviewed at later date said police eventually came to ask them to quiet down, but no one was arrested or made to leave the park.)

Similarly, two men who were sitting in Slack Plaza — a newly renovated public park — said they’d been there for at least an hour after the park’s closure and they hadn’t seen a single police officer.

Dustin Thomas, the man arrested the night before Regatta, said there is no doubt in his mind that the police, the city, and the court want people experiencing homelessness out of sight and out of mind.

“This is a totally discriminatory and biased practice,” he said. “They don’t arrest just anybody who happens to be in those parks after hours. They don’t search just anyone and shake them down.”

Thomas, who plans to fight the charge in court, said that if he can get access to the footage of the officer who arrested him, he’s confident he will prevail. But he said it doesn’t change the fact that he was manhandled in public by the police and put in jail for six days for simply complying with an officer’s request.

“It's like when you know somebody's wrong — dog wrong — but you can’t do anything. You want to say don’t touch me first and foremost. But you have to go through this whole process because he’s the one with the badge,” Thomas said.

The brother of a police officer, Thomas said he understands the pressures that come with the job and the need for policing. “I mean, there’s got to be a way to enforce the law that considers everyone’s basic rights.”

“I have respect for those that are carrying a badge and doing what they need to do out here in the community. But, we have to think about the outcomes that we all want out here in the community: unity, peace, and love – all these different things that show we care about each other. But when you get people like [Officer] Harper, just doing whatever he wants, it makes you wonder, who does he answer to?”