West Virginia Lawmakers Seek to Expand War on Drugs by Bringing Back Death Penalty

West Virginia politicians are labeling fentanyl a “weapon of mass destruction” and spreading misinformation about the substance in an effort to bring back the death penalty.

Jul. 9, 2023 • Written by Kyle Vass

Politicians talking about “weapons of mass destruction” invokes a mixture of nostalgia and dread for many Americans. The last time WMDs (and more broadly, “terrorism”) appeared in public discourse, it was to legitimize invasions of two countries in the Middle East – invasions that became increasingly hard-to-justify wars.

Hundreds of thousands of lives and trillions of dollars later, America is still coming to terms with being sold a false bill of goods. Even some staunch Republicans, the party that pushed most vociferously for war in the wake of 9/11, now criticize America’s legacy of involvement in conflicts beyond its borders.

In West Virginia, lawmakers are reviving these terms to gin up support for another war: the war on drugs. In recent years, some lawmakers have spoken about fentanyl the way former attorney general John Ashcroft spoke about the infamous weapons of mass destruction that Coalition forces never found in Iraq.

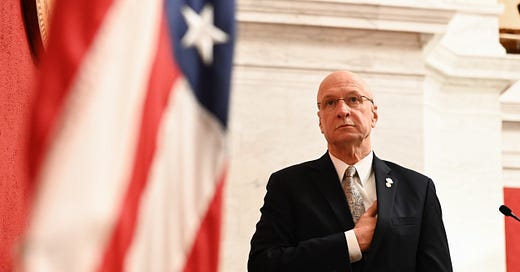

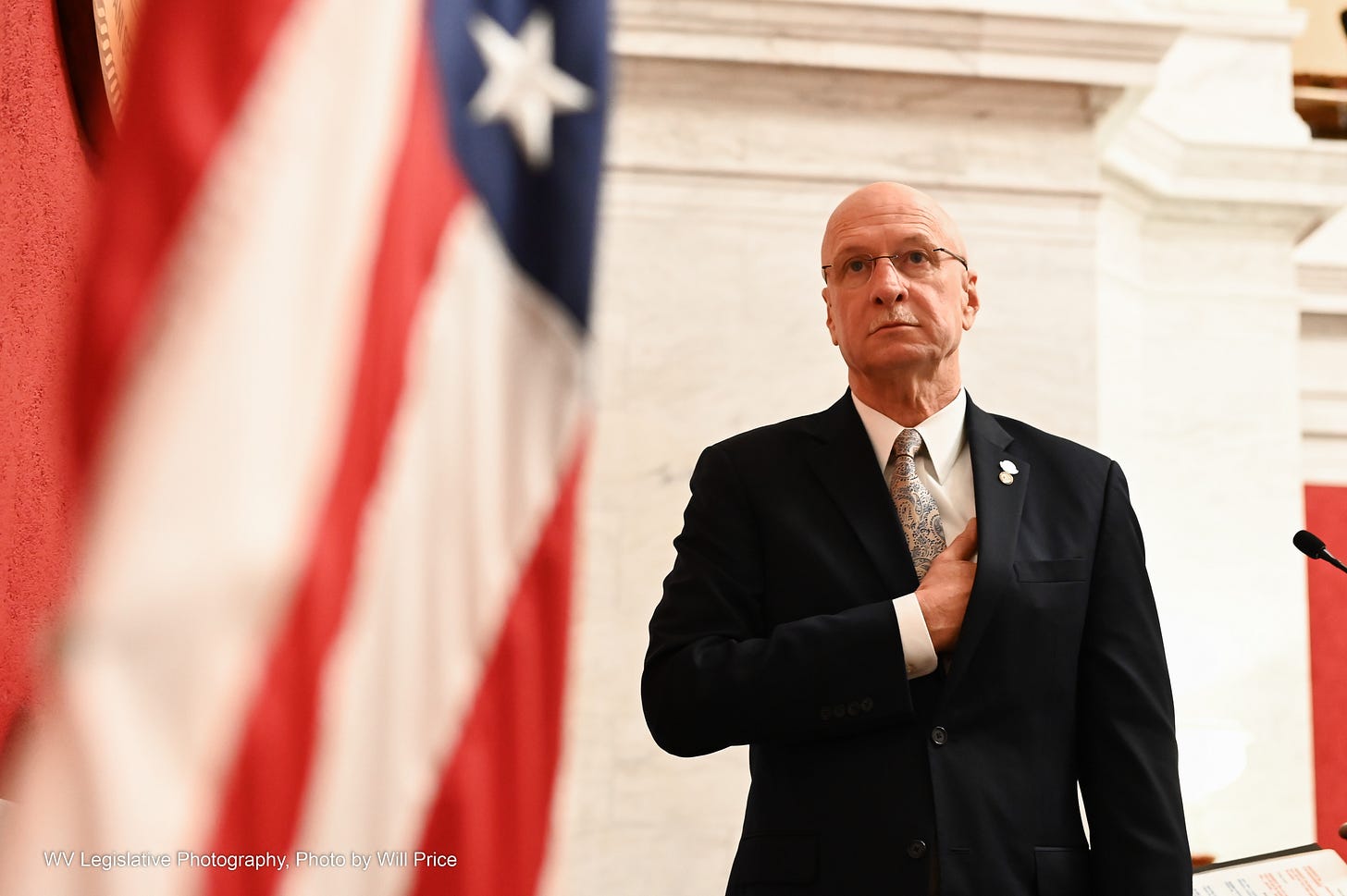

Now Senate President Craig Blair, just as leaders do in any war, is creating a justification for the government to commit state-sponsored murder. Blair recently called for the resurrection of the death penalty, abolished in West Virginia in 1972, for people convicted of certain drug crimes. It’s the most radical option politicians have put forward in years, but it’s also the natural progression of the escalating rhetoric and misinformation spread by government officials and the media alike.

In the 2022 Legislative Session, Delegate Mark Zatezalo (R – Hancock) told fellow lawmakers that fentanyl is such a threat to public safety that if someone were to “open a brick of it on the streets of Huntington” it would “kill everyone.” Last year, Delegate Bill Ridenour (R – Jefferson) introduced HB 2916: “Relating to terrorism.” – a bill that would have added “illegal drugs such as fentanyl” to a list of weapons of mass destruction, just behind nuclear and radiological weapons.

Ridenour, who served in the U.S. occupation of Iraq, included language in his bill that would have made “membership in domestic terrorist groups, specifically including the entity known as ANTIFA” a felony carrying a three-year prison sentence. In a single bill, the lawmaker sought to tidily connect the foreign enemies he fought in Iraq to his political opponents and people who use drugs. Despite failing to pass, the bill was a significant escalation in the legislative discourse on fentanyl: a prequel to Blair’s calls for state-sponsored murder.

Compassion Erodes

Current public discourse around fentanyl stands in contrast to a not-so-distant past where communities in West Virginia served as backdrops for stories about recovery. The fact that the overdose crisis is decreasingly affecting the white middle class is driving a downturn in compassion, experts interviewed for this story said.

Across the country, communities that track health outcomes for unsheltered people reported a significant uptick in overdose deaths from 2021 to 2022, as much as a 64% increase in King County, Washington. The latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows overdose death rates for Black people have increased 44% nationwide.

As the demographics of who is dying shift, so does the level of compassion in courtrooms, recovery programs, and even in healthcare settings. “Those doctors treat you like you’re a terrorist.” Robert Yost, who has experienced homelessness and incarceration at various points in life, described visits to his local hospital as humiliating. “When you come and have an abscess from shooting [drugs], they won’t even touch you.”

Yost, who’s had reconstructive back surgery, lives with chronic nerve pain, an issue that gets dismissed due to his history. “I don’t need a pain pill. I have neuropathy, so I can’t feel my hands and feet,” he said. Despite getting on a medication for treatment and passing several urinalysis screens a year, Yost said doctors refuse to treat his nerve pain over fears of him being a “junkie.” Asked to sum up his experience with the hospital, Yost said, “They don’t care if you live or die.”

Craig Manns, a social worker for unhoused people in Huntington, said he often doesn’t want his clients to go to the hospital unless he’s with them, advocating for them to be treated with dignity.

“They won’t go back if they show up and get treated poorly.” Manns said these experiences lead to them getting sicker and avoiding treatment altogether – a statement that echoes findings of a 2021 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report on Charleston’s HIV outbreak.

In places like West Virginia that have been hit hardest by the overdose crisis, it’s easy to forget that there was a time before fentanyl, opioid trials, reports about pill mills, and recovery. Discourse around the early days of the opioid crisis focused largely on the same hot topics of today: blaming Mexico and an “unsecured border” for America’s public health crisis.

In 2007, Huntington residents were shocked when 12 people died in a six-month period due to overdoses deaths. Back then, two deaths from overdoses a month in a small town seemed like a lot to people because it was. The town had only reported four heroin overdoses in the six years leading up to this event.

The string of deaths caught the attention of the national media, including Sam Quinones. Quinones at the time was writing for the Los Angeles Times. He wrote about the series of deaths as part of a three-part story on the rise of Mexican-sourced heroin in the United States. Quinones, who would go on to write a seminal book on America’s opiate crisis (Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic) and testify in front of the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions as an expert on drugs, was drawn to Huntington.

His article “Black tar moves in, and death follows” told the tale of a city overrun by a type of cheaper, more accessible form of heroin than previously available. Huntington’s Police Chief Skip Holbrook told Quinones that prior to these deaths “we didn’t even consider heroin” an issue. Even though like many residents, the police chief was stunned by a wave of heroin, opioid overdoses in general across the state were skyrocketing at the time. On average, overdose deaths related to opioids in West Virginia had been climbing steadily by about 20 percent each year in West Virginia since 2001; almost entirely on prescription drugs. In 2007 alone, 495 people died from non-heroin-related opioid overdoses.

By comparison, only 22 people died of a heroin overdose in that same year including the 12 in Huntington. The reporting about this tragedy homed in on the notion that heroin – a drug previously thought too exotic to exist in small town America – had made its way to a town of 50,000 people.

But in doing so, Quinones focused on a drug that accounted for only 22 of 412 opioid overdose death that in a state that would become ground zero for America’s opioid crisis. Instead of painting a picture that included the largely legal drugs that were killing 95 percent of the people in the state at a skyrocketing rate, Quinones (and several other reporters that would look back at this story when reporting about Huntington as town ravaged by the crisis) focused on a tragedy involving 12, white members of middle-class society who had died as the result of a foreign enemy: the “Xalisco Boys” – a Mexican drug cartel. Despite making up a fraction of the deaths in the area, the deaths stood out for how sudden and unexpected they were for friends and family members who knew the deceased.

As Quinones pointed out the doctors were being arrested and charged for overprescribing pain medication, people who were used to using pain pills (legally or illegally) were turning to heroin. But what’s missing in the reporting of these 12 deaths is the fact that nearly all of the people who passed away were white, middle-class people who were relatable to people in power. There were two former business owners, an electric company employee, and most notably a college freshman by the name of Adam Johnson.

Johnson, who died at 22, became the unexpected face of innocence lost for a town that would go on to have 28 opioid overdoses in a four-hour window in 2016. His story, and that of his grieving father would be told time and time again by national media outlets looking to pinpoint where the opioid crisis first started to get out of hand. As more stories of young people caught up in a crisis manufactured by pharmaceutical companies and the government playing regulator whack-a-mole flooded the airwaves, public sentiment towards drug use became more compassionate.

Governments began to explore more humane approaches towards drug use. Efforts to provide recovery and diversionary programs ramped up. Instead of outright sentencing people to jail for drug crimes, special courts were established to offer treatment programs in West Virginia, where one out of every ten people the state imprisons are charged with simple drug possession. With the rise of these programs came racial disparity.

The same sympathy that flooded the state when white, middle- and upper-class families were facing problems wasn’t as readily available for Black residents. Crystal Good, publisher of Black by God: The West Virginian, documented her own attempt to find recovery in the state as a Black woman. In a story for Scalawag Magazine, Good detailed attending a recurring recovery meeting where she attempted to find “the tools to work through both addiction and racism simultaneously,” – a task that proved challenging in the third least racially diverse state in the nation.

In these meetings, Good recalled being “constantly told [she] was violating the recovery room rules for talking about episodes of racism, and then praised for speaking so articulately.” In addition to these microaggressions, at one point Good was asked to hold hands with a person standing next to her: a man with the words “WHITE POWER” tattooed on his face. To Good, “recovery” was a concept offered specifically with white people in mind.

“The opioid epidemic of the '2000s, however, changed the public face of addiction from Black to white,” Good wrote “The tone of policy changed too — "lock up the (drug) criminals" softened to ‘addiction is a disease.’ It's the same old, same old: white folks get care; Blacks folks go to jail.”

And data from West Virginia correctional facilities and drug courts supports Good’s position. A Dragline analysis of drug court data from 2005 to 2023 shows a significant racial disparity in who the judges of the courts allowed into their programs. Judges denied applications from Black people 28 percent more frequently than their white counterparts. Courts denied half of all applications from Black people.

Those same courts denied only 36 percent of white applicants. The disparity in outcomes for this diversionary court are even higher than traditional courts with respect to the demographics of people held in state custody. A Dragline analysis of July 2022 data from correctional facilities showed that the percentage of Black people incarcerated in state correctional facilities is 3.6 times higher than the percentage of Black people in the state.

Taking the Blame

Courtney Hessler, who covered drugs and crime for the Huntington-based Herald Dispatch from 2015 to 2023, noticed that white people routinely faced better outcomes from trials and drug courts alike. “We covered drug court graduation ceremonies all the time and I only remember ever seeing a handful of Black people.”

Hessler said she started to notice sympathy for people affected by drugs favoring white, middleand upper-class people in 2016, around the time Huntington experienced 26 overdoses in four hours. “All of those deaths were pinned on a street-level (drug dealer) who was Black,” she said.

Bruce Griggs, as reported by Hessler at the time, had a scholarship to a Division I football program and was taking care of his family when he got injured and began selling drugs to support his family. Hessler’s story, “Hard fall led man to Aug. 15 dealing,” was met with anger; readers who were outraged that she could do a story de - scribing the difficulties that Griggs faced.

“It’s so wild that this street-level drug dealer who just happened to have gotten a bad batch got pinned for this when no other arrests were made,” Hessler said. “He had so much of his life ahead of him. And he just had to take the blame for whoever was higher than him.”

Griggs is currently serving an 18-year sentence in a federal penitentiary. Another case Hessler covered in her time at the paper was the trial of Joshua Plante. Plante was charged and acquitted of a murder in Huntington, but police also found 2.89 grams of heroin at a house where he was staying.

Prosecutors not only charged him with “intent to deliver,” they also sought recidivist sentencing, more commonly referred to as a “three strikes rule.” Despite beating the murder charge, Plante received life in prison for having what his defense counsel described as a personal use amount of heroin. Plante’s lawyer appealed the charge, arguing only violent offenders can be considered for recidivist sentencing under state law.

But between the time Plante was found in possession of heroin and when the state Supreme Court heard his case, the court had issued an opinion that all crimes involving heroin are “inherently violent.” In that case, State v. Norwood (2019), the court rationalized that, “From the moment of its clandestine creation, heroin is illegal, and is a silent scourge to our State.”

The court would later uphold this statement saying that it didn’t apply to the sale of prescription drugs. Plante’s lawyer pointed out to the court that a year before case ended up on their docket, the court had overturned a nearly identical case. In that case, the court decided that the defendant – a white man – wasn’t committing an act of violence when he was caught in the act of selling Oxycodone

But for Plante, the court doubled down on its position that the mere possession of heroin, unlike the actual sale of prescription opioids, was a violent act. For comparison, heroin makes up about 20 percent of the opioid overdoses in the state since 2015. Prescription opioids account for 80 percent.

The state and media rolling out sympathy when white, middle- and upper-class families are affected by drugs (and clawing it back when the problem affects anyone else) is a theme throughout American history, according to Matthew Lassiter, a University of Michigan history professor and author of the forthcoming book The Suburban Crisis: White Middle-Class America and the War on Drugs.

“This has been going on at least since the 1950s,” Lassiter said. “There will be this flare up of the idea that addiction is surging in white, middle-class America. It’s almost always linked to legal pharmaceutical abuse that spills over into the criminalized market. And then there’s this talk about how we must stop being so harsh.” That sympathy isn’t extended to people who aren’t white or don’t meet a certain socioeconomic threshold, Lassiter said. Much like West Virginia’s correctional facilities and drug courts, classism and racism are the nationwide norm when it comes to the war on drugs.

Instead compassion is reserved for “’otherwise law-biding citizens,’ which is code for white professional, middle-class youth.” According to Lassiter, blaming outsiders – usually Black people in cities or immigrants from Mexico – is a fundamental feature of the war on drugs. Citing one such instance in a research paper titled Impossible Criminals: The Suburban Imperatives of America's War on Drugs, Lattiser wrote: “In postwar Los Angeles, local media and law enforcement blamed ‘Mexican pushers’ for the narcotics trade and perpetuated exaggerated stories of Mexican American “juvenile gangsters” invading white suburbs to provide marijuana and heroin to teenagers.

“The nonpartisan California Federation of Women's Clubs demanded harsh deterrents for pushers who sought ‘new converts’ in affluent suburbia, an explanation that shifted blame for the postwar delinquency crisis from white law breakers to external villains.”

The same idea of the racialized “pusher invading white suburbia” was evident in the 1980s and 1990s when crack-cocaine laws disproportionately targeted Black men, forcing them into prisons for decades while letting their white counterparts go with a slap on the wrist. Attempts to reform drug laws or provide diversionary programs, Lassiter, said are equally fraught with classism and racism.

Groups like National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws and the ACLU, he said, centered stories of young, white college students facing years in jail for marijuana possession.

For Lattiser, the decision on who gets diverted from the criminal punishment system and who gets incarcerated – or in Blair’s proposed legislation, executed, -- comes down to some of the least qualified people to make that decision. “Of anyone, who should be less in control of those decisions than cops and prosecutors?” he said.